Success factors of watershed management in Ethiopia

In a major global effort to enhance natural resource management, Ethiopia and other countries have invested heavily over the last two decades in a participatory approach called “integrated watershed development.” The Ethiopian government introduced it in the early 2000s (following prior investments in soil and water conservation), with the aim of curbing widespread land deterioration brought on by such pressures as excessive tillage and overgrazing.

A defining feature of this approach is its community orientation, with emphasis on responding to local needs, while ensuring sustainable land and water management. Since government support for the approach remains strong, it is very important to identify best practices from past experiences, which can inform and improve future actions. In 2011, for example, integrated watershed management was the centerpiece of the Ethiopian government’s pledge to restore 15 million hectares of degraded land, as a contribution to the Bonn Challenge.

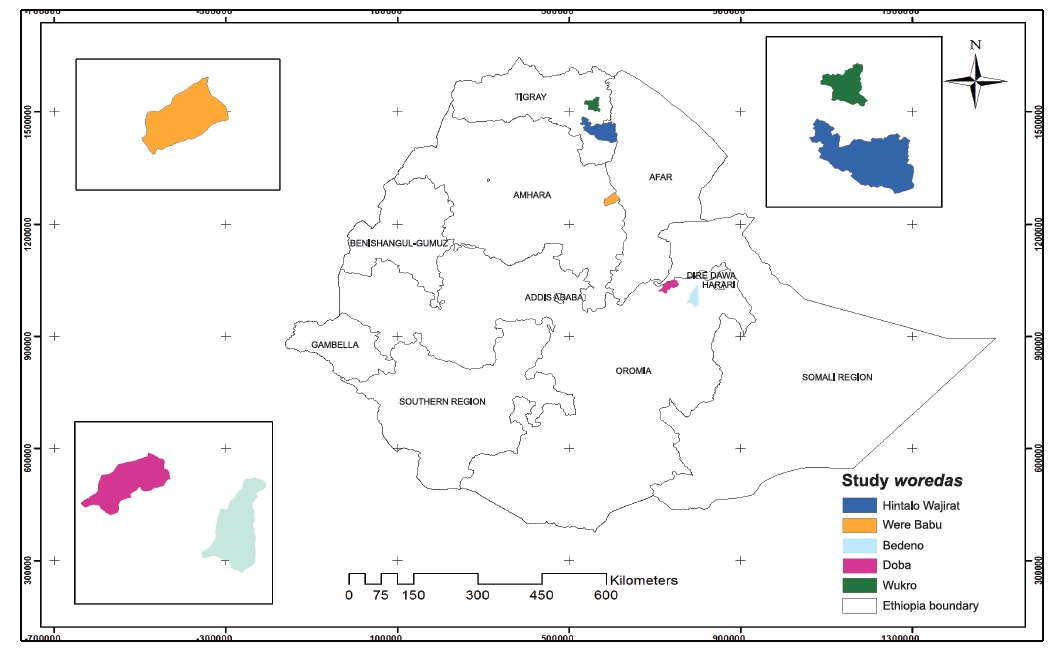

To provide information that can help guide such initiatives, scientists at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and Ethiopia’s Mekelle University undertook a comparative study of integrated watershed management in Ethiopia. A new IWMI Working Paper reports the results, derived from work in six watersheds of the Tigray, Amhara and Oromia Regions.

According to farmers and other community members surveyed, integrated watershed management appears to have been effective in all six cases. Respondents perceived the approach to have been useful for conserving natural resources, raising crop-livestock productivity and enhancing livelihoods. Farm incomes and food security were also reported to have improved by about half, on average.

In some watersheds, the risk of crop failure due to moisture stress and climate shocks was considered to have fallen by nearly a third. Soil erosion was also perceived to have declined by differing degrees across the six watersheds. Respondents further noted improvements in the restoration of land cover, with large differences between the three watersheds deemed to be successful and those considered less successful.

The factors that help explain such variations are diverse, ranging from biophysical conditions to the institutional and socio-economic setting. This underlines the need for multidisciplinary research in support of watershed development.

The hydrological and geological profiles have a particularly decisive effect on success, determining the rate of groundwater recharge, for example. Watersheds with permeable lithology (e.g., sandstone or alluvial deposits) and a concave shape show good upstream-downstream hydrological linkages, while the opposite is true in areas dominated by limestone lithology. Such factors, including both soil and bedrock conditions, are therefore a first consideration in selecting sites for investment.

Local communities can enhance these conditions through appropriate local management of natural resources. This is another reason to ensure strong support for learning and capacity building aimed at empowering watershed management committees.

The lead author of the working paper, Gebrehaweria Gebregziabher (an IWMI research economist, based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia) and the co-authors recommend the best practices listed as follows:

- Link physical and biological conservation with activities aimed at generating income and improving livelihoods.

- Tailor technologies to the prevailing agroclimatic, biophysical and socio-economic conditions.

- Promote community participation with adequate technical and financial support.

- Develop guidelines for the collection of baseline data, and monitoring and evaluation of water management interventions.

The authors further suggest that introducing improved seeds and better animal feed or breeds can deliver quick gains, ensuring positive returns for farmers in the first few years of watershed development, when impacts on natural resources may not yet be visible.

Read the IWMI Working Paper:

Gebregziabher, G.; Abera, D.A.; Gebresamuel, G.; Giordano, M.; Langan, S. 2016. An assessment of integrated watershed management in Ethiopia. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute (IWMI). 28p. (IWMI Working Paper 170).