Striking a balance between nature and development

“Connecting people with nature,” the theme of this year’s World Environment Day, is more complicated than it sounds, especially in the management of water – nature’s lifeblood.

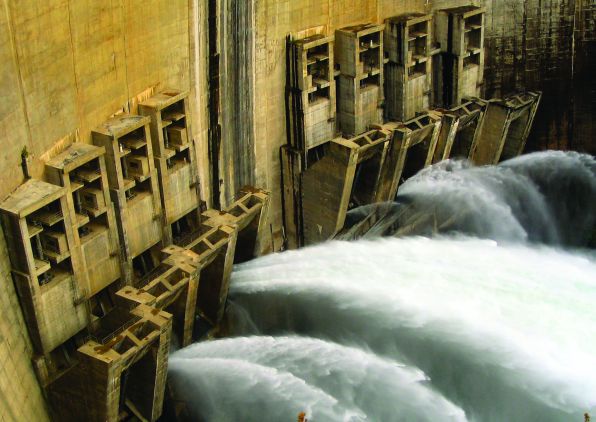

Photo: Matthew McCartney/IWMI

To manage water for human benefit, societies build levees, dams, irrigation channels and other infrastructure. Globally, investment in this activity has increased enormously during recent decades and is set to expand in the near future. Although such investment contributes importantly to economic growth, it typically also comes at a cost to the environment and to people, often the poorest, who depend on natural resources for their livelihoods.

Since the mid-1990s, we have gained a better understanding of ecosystems and the critical services they provide – from reducing floods to underpinning fisheries and supporting healthy soils. However, population growth and rapid development in many countries are placing more demands than ever on natural resources. Balancing the need for water, energy and food security, while preserving ecosystems and their benefits, is increasingly a challenge.

Nature-based solutions

To help respond, International Water Management Institute (IWMI) has taken part over the last three years in the project WISE-UP to Climate (Water Infrastructure Solutions from Ecosystem Services Underpinning Climate Resilient Policies and Programmes). Part of the German government’s International Climate Initiative, the project seeks to demonstrate how ecosystems can provide “nature-based solutions” that contribute to climate change adaptation and sustainable development. The aim is to gain insights into how we can combine built infrastructure with natural infrastructure,” such as wetlands, floodplains and watersheds, for the benefit of all. IWMI’s participation forms part of the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE), supported by the CGIAR Fund.

Photo: Nana Kofi Acquah / IWMI

In this collaborative effort, IWMI is working with the Basque Centre for Climate Change and the University of Manchester in the UK on analysis of investment in ecosystem infrastructure. The UK’s Overseas Development Institute is examining the political economy of water infrastructure decision making and governance. And the project leader, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), is overseeing “action learning,” aimed at strengthening the use of evidence and tools in policy making, decision making around infrastructure, and consensus building. The African Collaborative Centre for Earth Science Systems, in Kenya, and Ghana’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research Water Research Institute are engaged in the project’s case studies, with a focus on capacity building and communications.

The project covers two major river basins: the Tana in Kenya and the Volta in West Africa. Both have considerable built infrastructure and plans for constructing more dams and reservoirs. “One future trajectory is to simply carry on building large infrastructure, particularly big dams,” says Matthew McCartney, leader of IWMI’s Water Futures research group. “However, we’re trying to demonstrate how also investing in natural infrastructure will assist with adaptation to climate change impacts.”

Tackling tradeoffs

IWMI’s first role was to define “benefit functions” – essentially quantifying the relationships between river flow and ecosystem services. Examples of useful ecosystem services in the Tana and Volta basins are floodplain fisheries, flood recession agriculture, reservoir fisheries, estuary fisheries, cattle grazing on the flood plain and sediment transport out into the ocean (the latter is beneficial in the case of Tana, as it helps maintain beaches that are valuable to Kenya’s tourism industry). Institute scientists then modeled flow levels under different climate change scenarios to assess potential impacts on ecosystems and their benefits.

“For each ecosystem service, we looked at the link between flow and the magnitude of service provided,” says McCartney. “That information was fed into an optimization model run by the University of Manchester. They ran thousands of scenarios, incorporating the built infrastructure and its operation, and extracting the benefits and trade-offs in each case. This enabled them to, for example, assess tradeoffs between hydropower and floodplain fisheries for a wide range of possible futures.”

Action learning

One important lesson learned from the project is that relationships are not always easy to predict in such complex systems and can sometimes be counterintuitive.

In the Tana basin, for example, investing in upstream nature-based infrastructure, such as soil conservation measures, will reduce the sediment entering the river and so reduce reservoir siltation. However, if the local hydropower company uses the additional reservoir storage gained to simply maximize hydropower production, this will reduce water available to downstream ecosystem services, such as floodplain fisheries.

Photo: Georgina Smith / CIAT

Thus, planning and management need to be comprehensive, factoring in the full range of benefits and the intricate trade-offs between them. By including analysis of how decisions are made across the basins and by holding regular “action learning” events to share and discuss findings with stakeholders, project researchers hope to motivate power companies, governments and other decision makers to consider alternatives for basin and national development that make use of natural infrastructure.

“Dams and other built infrastructure are essential for socio-economic development,” says McCartney. Through WISE-UP and other projects, IWMI can influence future planning and investment in ways that continue to facilitate economic growth but are more equitable and sustainable.